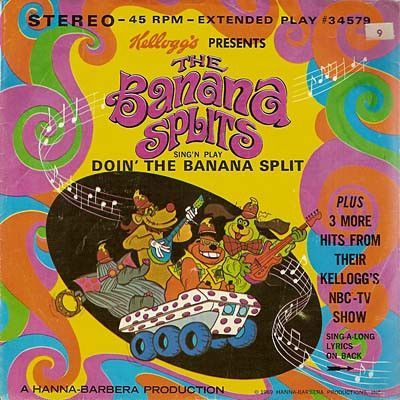

This is the story of a boy and his robot, but we’ll get to that. To begin we need to understand there was once a time when cartoons were serious business thanks to astounding financial and viewer numbers. A US statistics report from 1966 revealed that each episode of one Saturday morning cartoon called: “Superman/Aquaman snares 1,000,000 men, 1,000,000 women 1,500,000 teenagers and 6,510,000 children.” It then highlighted a new series called the ‘Banana Splits’ was to be “telecast every Saturday for 50 weeks, under Kellogg sponsorship, at a reported tab of $5-million…” That Five-mill today is just short of $50 million…for sponsoring an hour a week cartoon show.

Since the 80s it’s obvious that many modern cartoons are produced to sell a line of toys featured in the show – think Transformers and He-man. The above report makes it clear that ‘toons were always used by big business to sell something – and in 1966 that something was cereal. For their part Kellogg’s not only sponsored the Banana Splits, but having invested so much the company used a two-pronged attack by tying both products together when they branded this kooky band of animals all over their cereal boxes and in-box giveaways. Kellogg’s clearly saw this substantial investment would reap great rewards.

This massive investment and these viewer numbers triggered a short-lived Cartoon war in the 60s between America’s three main broadcasters, ABC, NBC and CBS. For years these stations had been airing a mix of new and recycled cartoons on Saturday mornings, with a few proving real winners for ABC. Beatlemania ensured a cartoon featuring the 4 mop-topped popstars drew a huge crowd, leaving the other stations to try and find something that could eat into this show’s dominant market share. 3rd placed CBS allowed a hungry young executive called Fred Silverman to try something new. Silverman began by decreeing the station would no longer air reruns or tired shows that had failed to find an audience. Issue #26 of the ‘Television Age magazine’ that year noted his new outlook:

“This year, CBS, in an effort to regain its leadership in children’s programming, is expected to spend close to $7 million on seven new half-hour animated color cartoon series.”

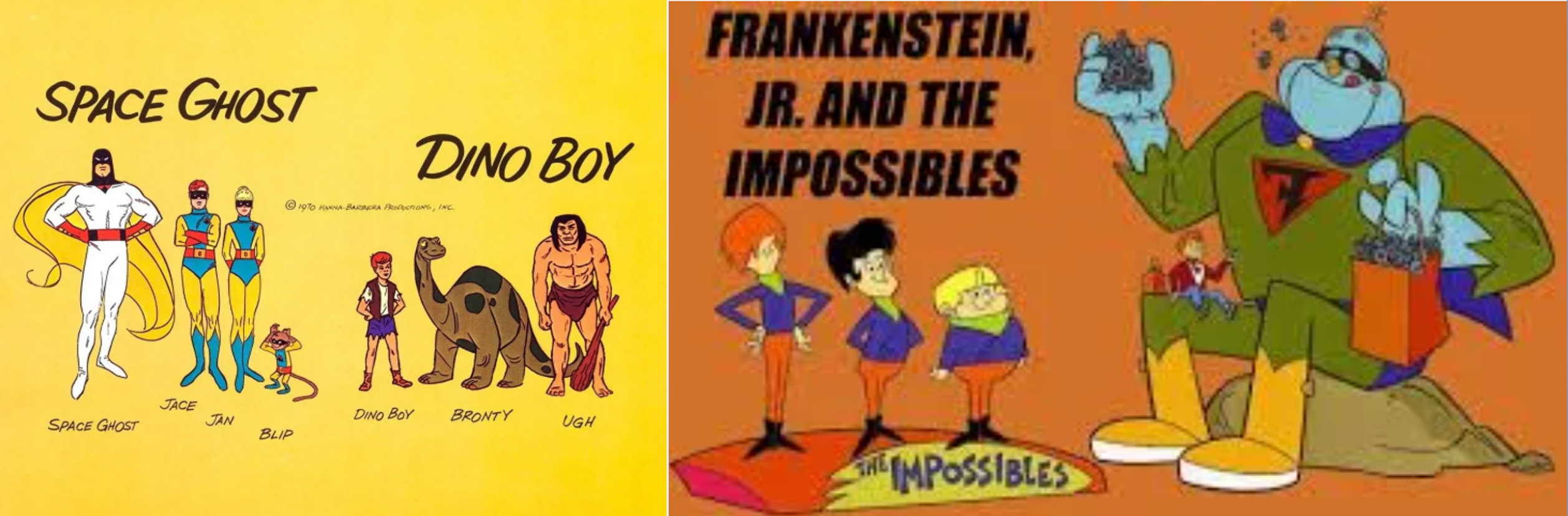

To achieve this Silverman talked to his cartoon suppliers and ordered all-new action series designed not only to take on ABC, but to dominate Saturday mornings from sunrise until at least 2 p.m. in the afternoon. This list included The New Adventures of Superman, The Lone Ranger, Space Ghost and Dino Boy, and starting off this line at 10am each morning appeared a show that would mix the Beatles pop-world with the current monster craze sweeping the nation, Frankenstein Jr. and the Impossibles.

These cartoons would also lean heavily into a new feature creeping into many cartoons of the day, two totally separate storylines. The Television Age explained that as well:

The division of each half-hour into three, or sometimes four, independent segments is one of the most characterize features of children’s cartoon programming. “If you make too many half-hour shows, you run the risk of losing the children’s attention and their changing to a competitor,” said Edwin Vane, ABC’s director of daytime programming.

The thinking was simple. Kids would switch channels if they didn’t connect to what was on, so by shortening storylines and having at least two different characters, there was a good chance they’d hang around and watch one while waiting for the character they preferred… and I personally do recall watching the show and preferring the giant robot over the hippie-style Impossibles.

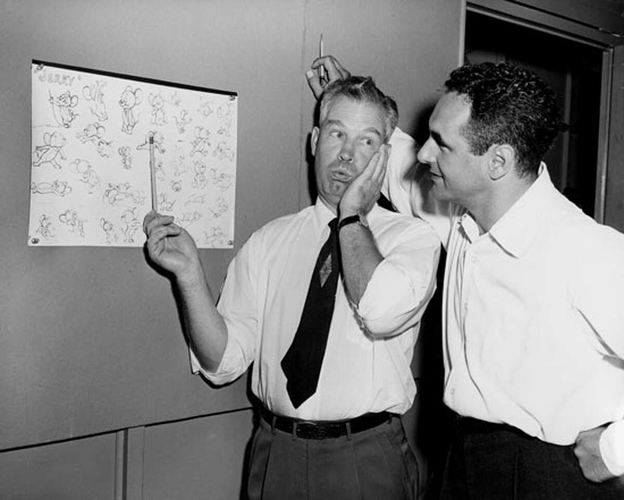

This new lineup proved so successful CBS rocketed to #1 with a 55% viewership for some shows, leaving the other broadcasters scrambling to update their own lineups. Viewership meant sponsorship and there were millions of dollars at stake, and the company at the heart of all this and raking in all-the-monies was Hanna-Barbera studios.

In 1966 they were producing as many as twenty cartoons a week for all three broadcasters, making them arguably the most important cartoon studio during the decade, with many of the cartoons they created becoming fan favorites and replayed for the next 50 years.

To name a few, between 1965 and 1967 HB were producing The Magilla Gorilla Show, The Peter Potamus Show, Jonny Quest, Atom Ant, Secret Squirrel, Sinbad Jr. and his Magic Belt, Laurel and Hardy, Space Ghost, The Space Kidettes, The Abbott and Costello Cartoon Show, Birdman and the Galaxy Trio, The Herculoids, Shazzan, Fantastic Four, Moby Dick and Mighty Mightor, Samson & Goliath and of course, Frankenstein Jr. and the Impossibles.

For those who don’t know the show, let’s hear from one of the two men who made up HB, Joe Barbera. Explaining how the show came about in his 1994 autobiography ‘My life in ‘toons’, Joe noted:

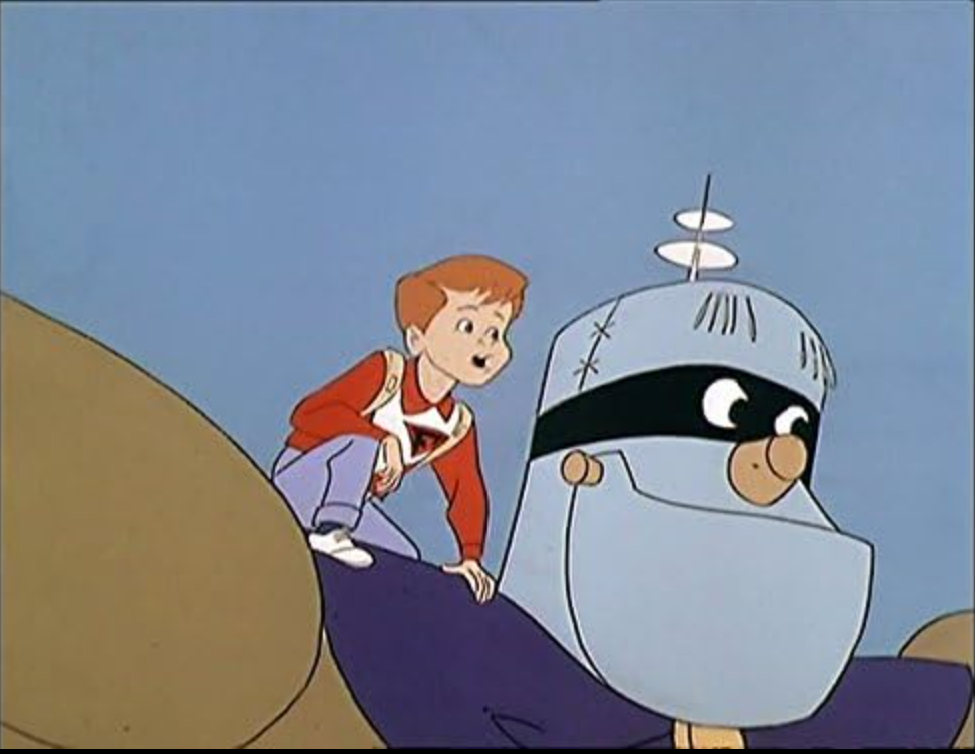

““Frankenstein, Jr.” and “The Impossibles,”… took the superhero genre in a more comic direction. Frankenstein, Jr., a fifty-foot-tall purple-caped robot, bore only the slightest resemblance to Boris Karloff and fought evil-doers with the help of his creator, a boy scientist named Buzz Conroy, who activated the robot by means of his radar ring. Sharing the time slot with “Frankenstein, Jr.,” “The Impossibles” were a teenage rock group (this was the year in which the tremendously popular bubble-gum rock band the Monkees, confected explicitly for television, premiered on NBC prime time) who were also — secretly — superheroes (“the worlds greatest fighters for justice”).”

Joe further explained that Fred Silverman rang him one day and asked if he could help create the new line of cartoons he needed, and it was during this phone call that Barbera came up with the idea of Space Ghost and some other titles. Remember, these cartoons were created to take on the all dominating Beatles show on ABC, thus the Beatle-esque long-haired rockers often shown during the episode singing one of their ‘hits’ during an action montage.

Barbera filled out some storylines and handed these ideas over to Joe Ruby and Ken Spears to pen a few scripts. These were handed in and CBS ordered a complete series. Next the normal vocal talent was hired for the show, but for the voice of the robot the producers called on one of the deepest and most distinct voices on TV. Ted Cassidy was a character actor who’d just become famous for playing a very similar roll to Frankie Jr. in the Addams Family tv show. A decade later he’d also voice the Incredible Hulk for Lou Ferrigno.

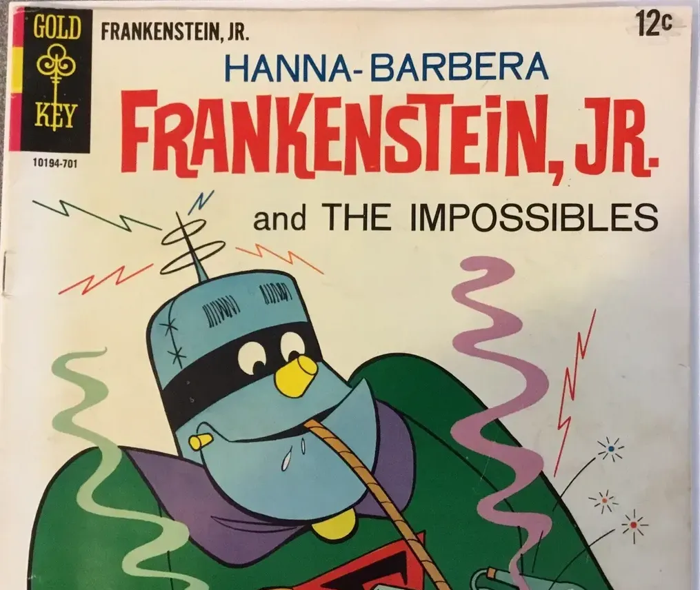

CBS then highlighted the show in a massive ad campaign. For example, MARVEL comics had a pull out, double-page ad announcing the new cartoon line up to the legions of comic readers at the time. Also released the same year, GOLD KEY published a single comic starring the giant robot to tie in with the cartoons release.

DID YOU KNOW? Though his name would never appear on any of these scripts, one of the staff writers for Hanna Barbera at the time was Superman’s co-creator Jerry Seigel. In later interviews Seigel explained he couldn’t recall working on the show at all, and further, he wasn’t sure what the hell he was doing working for HB as writing kid’s cartoons was so different from writing a superhero comic.

Inspiration had clearly struck the HB when creating Frankenstein Jr, but it turns out there was a very clear source for this. Japanese anime had begun to appear on US TV sets in the form of animator Osamu Tezuka’s ‘Tetsuwan Atomu’ (Astro Boy) and Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s ‘Tetsujin Nijūhachi-gō’ – itself based on a 1958 manga called Tetsujin 28GO. Tetsujin Nijūhachi-gō translates into English as “Iron Man No. 28″… so, not the snappiest of titles, but the cartoon about a giant robot built (and destroyed) in WW2 to fight the allies, and later was rebuilt as a weapon for peace became popular. Given an English title, the 12-year-old ‘Jimmy Sparks’ used a remote control to fight crime with the robot now renamed Gigantor.

2018’s ‘The Encyclopedia Of American Animated Television Shows’ reported another influence that’s often gone unnoticed. The influence of the popular live-action Batman series was felt most keenly in the regular use of humor in the narratives and such overacting villains as Dr. Spectro and Mr. Menace in the former component and the Fiendish Fiddler and the Terrible Twister in the latter.

I feel these resemblances are there for all to see, and just like the Batman TV show, this story about a boy and his giant robot also gained support amongst the growing pop-counterculture of the late 60s. Unfortunately, it hit screens at the entirely wrong time and so became the focus of a growing outrage over violence on TV. One viewer wrote that the “language and action are both rough and brutal.” About “Frankenstein Jr. and the Impossibles…The animated cartoons are composed of ugly monsters in ugly situations. It is a noisy show which is almost plotless.”

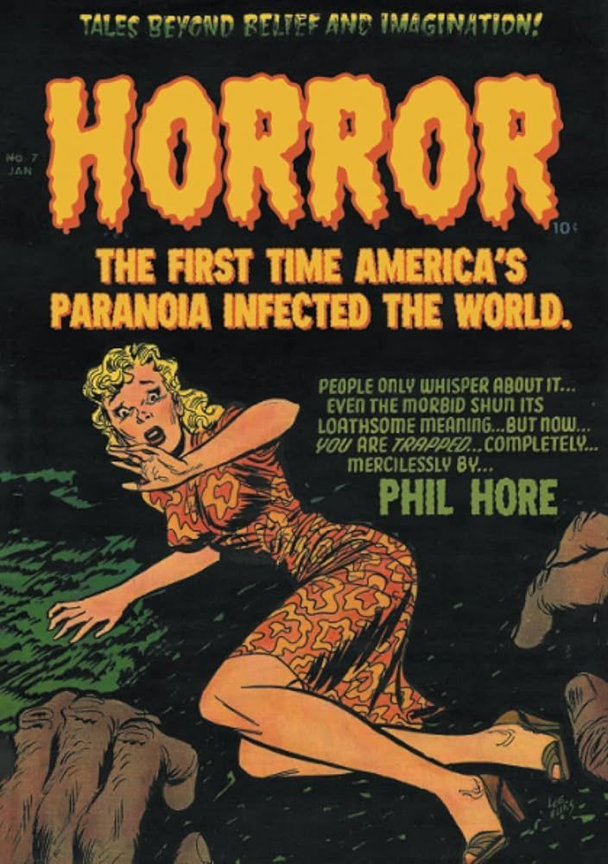

In my book HORROR I explain how every generation seems to have its problematic media. Today there’s a concern computer games are too violent, in the 90s it was rap music; in the 80s it was heavy metal and of course the late 70s it was Dungeons and Dragons that came under scrutiny of the puritans.

In the 1950s horror and crime comics were being blamed for a new social woe called ‘juvenile delinquency’, and just a decade later came cartoons. In the 1960s TV had become so invasive that it was considered a member of the family, and it did not take long for interest groups to start recoiling from the violence they saw in the cartoons being rolled out for kids on Saturday morning. Violence among teenagers and school-aged students was on the rise, and the only possible reason for many was TV. Their protests against cartoons soon became so loud, in 1972 the United States Surgeon General deemed television violence as a public health problem.

In 1967 The Catholic Transcript newspaper ran an article ‘PROBLEMS NOT KIDS’ STUFF IN TV’S ‘MINI-WASTELAND’. It when on to explain:

The “mini-wasteland” is Saturday morning television (with a steadily increasing spillover into Sunday morning), featuring cartoons, cartoons and, in between those, more cartoons. WHILE MANY of them feature violence, horror and tasteless slapstick, the major concern appears to be over the sheer waste of time rather than over the cartoons’ real or imagined ill effects. “Cartoons are more harmful because of their banality than anything else,” according to Dr. A. D. Buchmueller, executive director of the Child Study Association of America. There are, to be sure, continued protests about cartoon violence (“People are dying all over the place and no one mourns,” said one TV producer. “No one dignifies death with grief. What does this do to the child’s idea of the value of human life?”), but the main criticism seems to be that on Saturday mornings when as many as 16 million viewers under the age of 12 are watching they have, with very little exception, nothing to watch but cartoons.

Their concern was not just the violence, but the passive nature of simply watching TV for hours with little interaction was stunting the growth of children, physically and mentally. They called for sweeping changes, with more educational programs replacing the action, flashy and noisy cartoons. The article ended with a warning the: “mini-wasteland will not be adequately irrigated, suggests TV Guide, until parents really become concerned about it.”

In 1968, Sign Magazine ran an article about how effective these actions against cartoon violence had become. “Finally, there will be a change for the better in children’s programing. The Saturday morning block of cartoon shows is probably the most offensive in television. Long before the recent spate of political assassinations, parents were complaining about the excessive violence their pre-schoolers were being subjected to in what used to be called “the funnies.” Shows like “Frankenstein, Jr., and the Impossibles…have been the regular imaginative food of American youngsters almost from the time they left the crib. It is not unusual for youngsters to know the plots by heart, so often have they seen them. Whether they imbibe a taste for violence through these cartoons, I don’t know, but the outsized, fantastic creatures inhabiting these shows certainly can play havoc with a preschooler’s unformed imagination.”

1977’s ‘The ultimate television book’ by Judy Fireman was in no doubt who was to blame for the rise in TV violence. “Hanna-Barbera has been the major producer of television cartoons since the late fifties …If any studio is to blame for setting trends in television cartooning, it is Hanna-Barbera – for pioneering the excessive use of violence…”

Partly as a response to the growing call to do something about violent cartoons, and partly due to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Robert F. Kennedy and let’s not forget the murder that gave him his job, the assassination of JFK, in 1968 President Lyndon B Johnson created the ‘U.S. National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence.’ Congress began “a Task Force on the Media to investigate the effects of media portrayals of violence upon the public and the role of the mass media in the process of violent and non violent change…” One of the key witnesses they called before them was the President of CBS, Frank Stanton. What occurred next would be released to the public in 1969 inside several volumes named ‘MASS MEDIA HEARINGS Vol 9a – A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence.’

Congressman Hale Boggs was the man to ask Stanton about violence in his station’s new cartoons:

“I call to your attention the following, do you watch these programs?”

Mr Stanton: I see them from time to time. I don’t spend every Saturday at the television set.

Congressman Boggs: But you have seen them.

Mr Stanton: Yes.

Congressman Boggs: You have seen Moby Dick and the Mighty Mightor…The Space Ghost?

Mr Stanton: No.

Congressman Boggs: It is one of your programs?

Mr Stanton: I don t think it is any more.

Congressman Boggs: Why did you stop it”

Mr Stanton: We made a number of changes on Saturday morning. We have taken out four of the cartoon strips in the early morning as part of our program of changing our mix on Saturday morning.

Congressman Boggs: Why did you do that?

Mr Stanton: Everybody was having the same thing and we thought we would provide an alternative diet for one thing.

Congressman Boggs: Frankenstein Jr and The Impossibles?

Mr Stanton: Not on our schedule.

Congressman Boggs: No more?

Mr Stanton: Never was?

Congressman Boggs: So, listed here. Somebody made a mistake?

Mr Stanton: I may be mistaken, but I don t believe it was on the schedule.

There are dozens of books containing all these interviews – yet in this single conversation you can see Congress had just attacked the violence in Frankenstein Jr., and I have to point out Stanton was wrong. The cartoon was indeed part of his Saturday morning line up, and I believe here is why we only got 18 episodes. The show was cancelled by CBS to try and alleviate this growing social pressure against cartoon violence.

A victim of timing, this was not the end for Frankenstein Jr, as the cartoon would resurface a decade later attached to a new show, Space Ghost. These two old favorites had been revived to replace an expensive, live-action, stop-motion dinosaur show called ‘The Land of the Lost’ (that would get a big budget comedic remake in 2009 with Will Ferrel).

The show was a gamble to try something other than just a cartoon, and CBS executives watched as massive viewing numbers rolled in…for ABC. Despite all their efforts and creativity, Land of the Lost had failed to make any headway against their rival, so CBS went back to cartoons. However, times were changing…

By the mid-80s these blocks of Saturday Morning cartoons were starting to suffer from falling viewership numbers thanks to the distraction of various home media, like video games, VCRs and MTV. But like the classic monster it was based on, Frankenstein Jr. would be brought back to life once more when new cable channels like BOOMERANG began airing old episodes, ensuring the cartoon would be seen by a new generation. This explains why such a minor, short run cartoon is still treasured by fans today.

DID YOU KNOW: As far as my research can find, the name Frankenstein Jr. actually first appeared in Famous Monsters of Filmland #12 in an article about the ‘Son of Frankenstein’.

The above article was written by Phil Hore. Phil Hore has written for newspapers and magazines across the globe, and has worked as an educator at the Smithsonian, the Field Museum and the Australian War Memorial. He writes history, science and science fiction, and often finds all three meeting each other on the page