In the 1950s and 1960s, low-budget horror films brought massive profits to Hollywood. Horror movies once dominated the box office, but since then, directors and studios have had to get more inventive to attract audiences. Then, in theatre’s all over the country, people started using all sorts of tricks to make their movies more memorable.

Here is a brief history of some of the most iconic gimmicks in horror movies, from hypnotists to life insurance to free vomit bags.

A classic horror film must do more than scare you on the outside; it must also disturb your innermost thoughts. Before becoming Terror in the Haunted House, this was the goal of Psycho-Rama in My World Dies Screaming. Subliminal imagery was first used in Psycho-Rama to scare viewers more effectively than ever before.

Not long enough for an audience member to consciously notice, but long enough to make them uncomfortable, images hideous ghouls, skulls and words like “death” would flash across the screen. The public and the film industry didn’t take to Psycho-Rama, but some horror filmmakers, like William Friedkin in The Exorcist, have used the same quick imagery to great effect.

William Castle, a director who became famous despite, rather than because of, his work, relied on shock and schlock to attract audiences to the movies. His films had all the horror, gore, terror, suspense, and suspenseful camp that audiences loved at the time. His marketing skills were unparalleled, and the tricks he added to each film are still talked about by horror fans today.

His most well-known antic was buying life insurance policies for everyone in the audience of his show Macabre. If you were so terrified that you passed out in your seat, your family would receive $1,000 from a real policy backed by Lloyd’s of London. Who among us wouldn’t want to take a chance on a deal like that? Naturally, the policy did not apply to anyone with a preexisting condition or to anyone in the audience who committed suicide while watching the film. Understandably, Lloyd’s would set a limit there.

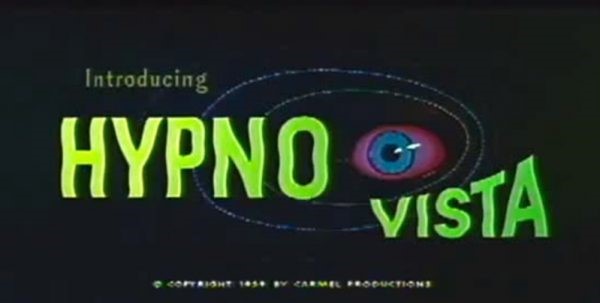

To what extent can you differentiate your run-of-the-mill horror flick from the rest? Get them under your spell. So, Hypno-Vista came into being. As a marketing gimmick, American International Pictures’ president James Nicholson proposed showing a lecture by hypnotist Dr. Emile Franchel before the screening of Horrors of the Black Museum, which centred on a hypnotizing killer.

Dr. Franchel tried to hypnotize the audience for 13 minutes to get them more into the story by explaining the science behind hypnotism. It was a gimmick that got people into theatres in 1959, but now it just seems too long and boring. In addition, writer Herman Cohen claimed the lecture had to be cut from repeat TV broadcasts of the film because it hypnotized some viewers.

Even though it’s not the most gimmicky of gimmicks, the fact that no one was allowed into the theatre once the screening of Psycho had begun garnered a lot of attention at the time. However, the Master of Suspense is less concerned with publicity and more interested in providing a good show for his fans. He didn’t want people to miss Janet Leigh’s part and feel duped by the movie’s marketing because she dies so early on.

However, the ground-breaking French horror film Les Diaboliques (1955) also implemented a similar policy for publicity purposes. At the time, moviegoers could simply walk in whenever they pleased, so the sight of a director, especially one so skilled in the art of publicity, who was insistent on arriving on time was sure to pique their interest.

The “fright break” that William Castle offered in his 1961 film Homicidal was another classic gimmick of his. The film would be racing towards its bloody climax when a clock would suddenly appears on the screen. Scared patrons could leave the theatre within 45 seconds and get their money back. But there was a caveat.

Those in the audience who gave in to their fears and left the theatre early were relegated to the “coward’s corner,” a yellow cardboard booth guarded by a poor sap worker. Then they made them sign a sheet that said, “I’m a genuine coward,” before returning their cash. Most people decided to grit their teeth and endure the horror on the screen rather than risk such shame.

The audience is given control of the film’s outcome in William Castle’s most interactive schlocky horror gimmick. Castle came up with the idea of a “punishment poll” so that moviegoers could have their say in what happened to the Mr. Sardonicus cast. Visitors were given a card depicting a thumb that, when illuminated by a special light, would signal their entrance into the theatre. With a “thumbs up,” Mr. Sardonicus would be spared, and with a “thumbs down,” he would be executed. Despite Castle’s assurances that the happy ending was already filmed, old Sardonicus never got the green light from moviegoers. Nonetheless, many people have doubted his claims because no competing ending has ever emerged. It seems likely that Mr. Sardonicus had only one possible exit.

Horror fans aren’t looking to be entertained so much as they are scared. In light of the film’s gruesome subject matter, it’s easy to see why the producers of 1970’s Mark of the Devil handed out free vomit bags to the audience. The studio advertised more than just the bags; it also claimed the film was rated V for violence (and possibly some vomit).

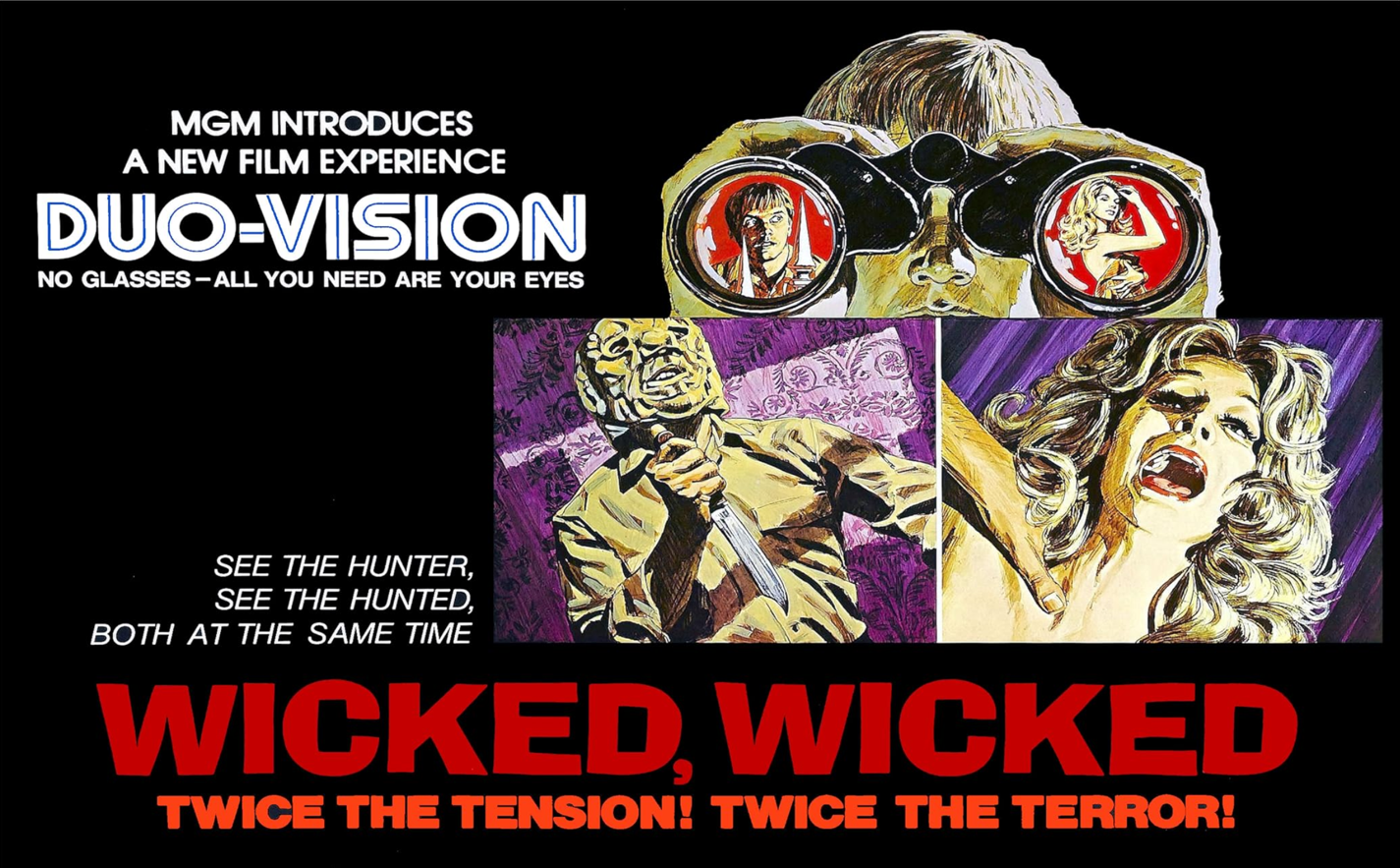

The new filmmaking method known as “Duo-Vision” was marketed as providing twice the scares for the price of admission. Of course, “Duo-Vision” is just marketing speak for “split-screen,” in which viewers see a movie from two different viewpoints simultaneously. This was done in the 1973 horror film Wicked, Wicked by switching between the perspectives of the killer and the people he murdered.

This sounds like it could be a great horror story premise, right? Duo-Vision was indeed used throughout the entire 95 minutes of the film, not just for the most terrifying scenes. The method had been used in other films, albeit rarely, before, most notably in Brian De Palma’s superior Sisters (1973), but never to this degree. Apparently, “Duo-Vision fatigue” sets in quickly, because the technique quickly lost favour.

Hammer Films, based in England, became well-known for its gothic atmosphere, liberal use of blood, and sensuality in its horror films throughout the 1950s and 1960s. American distributors like Warner Bros. relied on gimmicks to lure in audiences despite modest budgets and no major stars for their remakes of classic movie monsters like Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Mummy.

If you frequented New York’s drive-ins and grindhouses in the ’70s and ’80s, you probably saw a lot of content distributed by Aquarius Releasing, Inc. From martial arts to softcore to mondo movies to Italian crime pictures to international horror films, Terry Levene’s company dealt with it all. Aquarius always made impressive marketing materials for their films, but their campaign for “Dr. Butcher, M.D.” in 1982 has gone down in cult film history.

The 1980 Italian zombie-cannibal mashup “Zombi Holocaust” was renamed “Dr. Butcher” by director Levene, who also spliced in footage from a different horror film by documentarian Roy Frumkes. In addition, he decked out a flatbed truck with medical equipment and recruited marketing consultant Gary Hertz, then at New Line Cinema, to play the good doctor, who would “operate” on a victim (played by legendary zine maven Michael J. Weldon of “Psychotronic” fame) while fellow zine publisher Rick Sullivan shouted to astonished passers-by in Manhattan and the outer New York boroughs.

Fans of exploitation and horror from the 1970s will love Hemisphere Pictures’ “Blood Island” series. All filmed in the Philippines, the four B-movies (‘Terror is a Man’ (1959), ‘Brides of Blood’ (1968), ‘The Mad Doctor of Blood Island’ (1969), and ‘Beast of Blood (1970) share a common theme: evil experiments being conducted on the island of the same name.

Hemisphere also ran outrageous ad campaigns for the Blood Island films, such as the prologue for “Mad Doctor,” which urged audiences to drink what was billed as “green blood.” Before each showing of “Mad Doctor,” audiences were given packets of coloured liquid to simulate blood. The prologue’s narrator then went on an incoherent rant about the green blood’s hidden abilities, which included the ability to induce sexual arousal and the ability to perceive “a supernatural consciousness.” The play’s primary goal was to convert viewers into members of the “Order of Green Blood” by having them swear an oath that would make them immune to the “unnatural green-blooded ones without fear of contamination.” The latter may have been the case for some patrons, as producer Sam Sherman, who made the “Order of Green Blood” spot, reported becoming violently ill after consuming one of the blood packets in Fred Olen Ray’s The New Poverty Row: Independent Filmmakers as Distributors.

Warner Bros. decided that encouraging audience participation was the key to reviving interest in “Dracula A.D. 1972,” the second-to-last film starring Christopher Lee as Dracula from Hammer Film Productions in the United States. Similarly to the oath taken by the Order of Green Blood, American moviegoers were shown a short film titled “Horroritual” (also known as “The Oath”), which featured a cobweb-draped vampire who urged them to pledge loyalty to the Count Dracula Society (“so help me, Christopher Lee”). The society was real, and Dr. Donald A. Reed, who ran it, eventually expanded it into the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films, where the Saturn Awards are presented. Barry Atwater, who also played another memorable bloodsucker in the same year in “The Night Stalker,” which introduced Darren McGavin’s Carl Kolchak, played the on-screen vampire with a Lugosi accent.